A new planet discovery located 400 light years away in the constellation Cygnus, designated Kepler-78b, has provided a new challenge to planetary formation models. Orbiting at a distance of less than one million miles from the G-type (sun like) star, the planet completes one revolution in its orbit in only eight and half hours. Current theories of planet formation suggest that the planet would have not have formed so close to the star nor could it have migrated there. Part of a new class of planets that have recently been identified in date from NASA’s Kepler spacecraft, these planets all complete orbits around their stars in less than 12 hours. They are also small, on a similar scale to the Earth.

The discovery has been announced by a team working at the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics (CfA). “This planet is a complete mystery,” says astronomer David Latham. “We don’t know how it formed or how it got to where it is today. What we do know is that it’s not going to last forever.” Gravitational tidal forces will draw the planet ever close to the star. The final result of this shrinking orbit will see the planet ripped apart by the star’s gravity. That is predicted to occur within three billion years.

The challenge this planet poses for planetary formation theorists is the current orbit sits inside the diameter of the star when it was in a younger more swollen stage of its evolution. Could it have migrated inwards from a wider orbit? Not so according the team. “It couldn’t have formed in place because you can’t form a planet inside a star. It couldn’t have formed further out and migrated inward, because it would have migrated all the way into the star. This planet is an enigma,” explains Dimitar Sasselov.

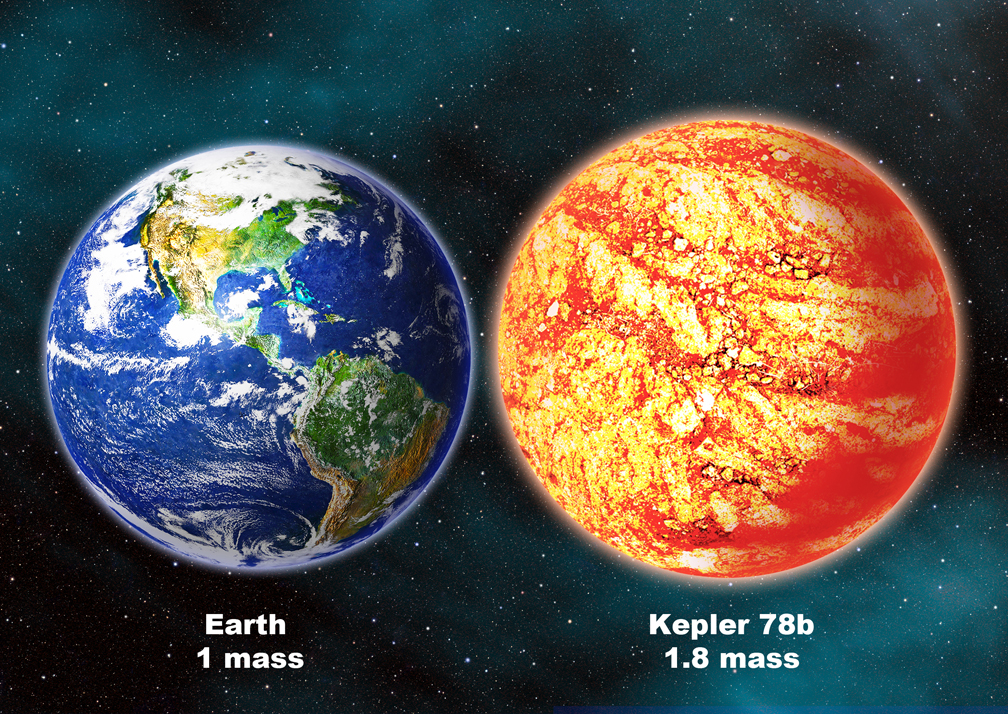

To add further fame to this newly discovered world, Kepler-78b is the first planet in the new class to have its mass measured and it is the first Earth-sized world found with an Earth-like density. At approximately 20% larger than the Earth, with a diameter estimated at 9,200 miles, the mass is approximately twice that of the Earth. This implies Kepler-78b has a density which is very similar to that of the Earth which suggests an Earth-like composition of iron and rock.

At 20% larger, and twice the mass, Kepler has a similar density to the Earth. Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA)

The Harvard team studied Kepler-78b using a newly commissioned, high-precision spectrograph known as HARPS-North, at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on La Palma. A second, independent team using the HIRES spectrograph at the Keck Observatory coordinated on the analysis, and the respective teams’ measurements agreed which increases the confidence in the result.

Headquartered in Cambridge, Mass., the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) is a joint collaboration between the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Harvard College Observatory. CfA scientists, organized into six research divisions, study the origin, evolution and ultimate fate of the universe.